Before drifting away to other matters I'd like to talk about another of Ralph McTell's songs, Barges, which must have featured on that lost cassette of the Apollo concert (see previous post) as I hear it in my head as voice and guitar, unadorned.

I emailed the leader of the folk band which may or may not feature the schoolfriend who lent me the tape thirty five years ago, asking him to forward my belated message of apology; there has been no response as yet. But, even assuming that the ill-advised tape dispenser has been correctly identified from the band's website, it may be that silence is his most effective rebuke.

In Ways of Escape Graham Greene describes bumping into a former schoolmate on his travels who clearly has no recollection of his vicious bullying of the writer, the behind-the-green-door headmaster's son, many years before. Greene's mild revenge is to make a promise, which he has no intention of fulfilling, to meet up properly on the return leg of his journey.

If this proves to be a similar situation then at least I can reassure my former schoolfriend, should he ever read this, that the absence of that tape now pains me too: the studio recordings aren't the same, especially in a particular instance which I'll discuss later.

Nevertheless, Tony Visconti's production on the original album version of Barges is well done: voice and guitar are not overwhelmed. It sounds like the only extra instrument is a recorder, possibly doubletracked, played by Visconti himself (if bassist Danny Thompson is in there, he's kept well in the background - a feat in itself).

And McTell's vocal is interesting: intimate, presumably close-miked, like Donovan's Starfish-on-the-Toast, he audibly strains to hit some of those bottom notes but Visconti was right to have retained a take which seems to convey both the adult's sense of care in handling those memories and the wonder and shyness of the child. This may have been further aided by the use of a £16 "wonder microphone" which Visconti favoured over the studio mikes costing thousands (I recall reading in Visconti's autobiography that an accidental "flutter" effect on T Rex's Jeepster was retained as it sounded better).

Microphones apart, I'm not sure of the provenance of another, perfectly good, recording of Barges - findable here - but McTell's delivery doesn't convey that same half-in-childhood effect as on the recording below:

Me and my brother returned to the waterThe whole seems beautifully judged. It's not knowing, exactly, although there may be a deliberate echo of Yeats's The Song of Wandering Aengus (Donovan recorded a setting of it the previous year) in the reference to "hazel twig wands." And while the distancing of "two small magicians" suggests an adult viewpoint, for most of the next two verses we are immersed in the boys' experience.

I saw a pike that was two feet long.

Two small magicians, each with a jam jar

Cast spells on the water with hazel twig wands.

Country boys catch tadpoles, dive into water

Made shy by their laughter, we wandered down stream

And summer rolled o'er us with no complications

'Cept thinking of Mama sometimes in dreams.

Stand by the drawbridge, waiting for barges

Waiting around for smiles from the man.

Lifting the bridge whilst watching the horses

Dragging the slow boats up the canal.

I do remember the times but no number

After the day, but before evening comes

Waiting for castles and kettles with roses

Painted on barges that sailed to the sun.

Oh, see the river run, that was by man begun

Open the locks, let the boats sail on,

Taking their castles and kettles with roses

With summers of childhood leaving smiles on the man.

The conclusion's "leaving smiles on the man" could seem slightly clever, the lock keeper transformed into the narrator, remembering the scene; it becomes less so when you consider the implication that the lock keeper's smiles may have come from an awakened memory of his own childhood in seeing the boys. In short, this has a lot in common with Hardy poems such as this one here or these two here; Larkin wrote that one of Hardy's themes was "time and the passing of time."

There's a slight ambiguity at the end of McTell's song, which may be about the net and the hazards of transcribed song lyrics rather than any deficiency in the composition as officially published. Do the "summers of childhood" feature in the cargo about to travel off or are we to understand that they are what has been left behind to offer consolation to the adult?

The absence of a comma after "roses" in the version I found online, plus another listen to the original recording, would suggest that he's saying that those summers too, have become so much freight, now bound elsewhere. McTell-as-narrator seems to accept this, whether actively giving his blessing or simply bowing to the inevitable: "Open the locks, let the boats sail on."

As some consolation can be derived from the act of remembering, presumably it's this which leaves "smiles on the man": it may only be a souvenir, but he has, nevertheless, salvaged something from the rush of time.

Unlike - to take an instance at random - that cassette of the 1975 concert, whose loss I lament not only for its barebones rendition of Barges but also an odd moment during the performance of McTell's elegaic Maginot Waltz when, during a lull at the end of one section of the song, a car horn is faintly heard outside.

In fairness to the sound engineer (whose name, according to the jocular Steve Jones, was "Pete-what're-the-levels-like-Shipton"), mixing was apparently being done during the broadcast, with no attempt to hide the fact that portions of the chat were being extended if a particular song wasn't quite ready - which suggests the programme was indeed being transmitted on the same night as the concert itself.

That accidentally overheard horn - even if anachronistic (the song tells of a last jaunt before two young men go off to the Great War) - has become part of the song for me: a little bit of aural punctuation - or possibly even a tiny hint of doubt, a single, barely heard, jarring note, like Chekhov's breaking string, amid the misplaced optimism of the times:

I told her we'd be home in a week or twoMaybe the mocked Mr Shipton knew exactly what he was about. Or more likely it's about that human (or possibly just male) need to create order and meaning from whatever random conjunctions

Me an' Albert and Lord Kitchener, we'd teach the Hun a thing or two

come our way, as in this entry in artist Ian Breakwell's diary:

The 18.30 train from London to Plymouth. In the dining car the fat businessman farts loudly and unexpectedly, and simultaneously by the side of the railway track, a racehorse falls down.I was both pleased and annoyed at the ease with which I located the above on the net, having thought it was my secret discovery, unnoticed by any other reader. Sad to report, it has been pasted in from an obituary; Breakwell died in 2005. I had a book of his diaries but hadn't kept up with his subsequent career, although a 1994 film collaboration with Motherwell Library's own Ron Geesin sounds intriguing:

we are taken to a variety show, but are only allowed to see the audience's reactions; the results are hilarious and touching.Thinking of further random sounds - a subject, it is far from unreasonable to suggest, not unadjacent to Mr Geesin's atom heart (ooh, clever) - I once taped Young Americans over some random recording on my little cassette player; on playback a second or two of a door opening slowly and squeakily segued into the sax intro quite convincingly - for me, ever afterwards, Young Americans just isn't Young Americans without it.

"Ain't there one damn song that can make me - shu-ut that doo-oor!"

And by a perfectly understandable associative process, I now call to mind that my immediate younger brother once had to stop taping a Roxy Music B side when our grandfather came into the room. I don't know whether he had voiced any objection or whether my brother had halted out of politeness anyway - although as this was a man incapable of registering a direct protest when the same grandson once unknowingly occupied "his" chair, instead hovering for the chance to rush over and reclaim it (my brother was about ten at the time), I must, on this occasion at least, grant a sibling the benefit of the doubt.

Anyway, because I played that abandoned compilation tape more or less nonstop one night when trying to meet a deadline for art school, the arbitrary cut-off point in Roxy Music's The Numberer became lodged in my head as an artistic decision, like the razoring of I Want You (She's So Heavy) on Abbey Road. And time has probably added its own white noise to that incomplete Roxy track. If I could find the cassette.

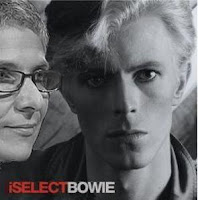

I'm aware that this entry may be displaying its own symptoms of degradation after that lit crit-type earlier half, but I can't quit without mention of a slight but haunting Bowie/Eno track, Some Are. I first discovered it on a CD edition of Low (produced, like Barges, by Tony Visconti), but it was later included in a Bowie compilation (above) originally given away with the Mail on Sunday (top columnist Mel P threatened to leave unless her image was incorporated into the cover; she was removed from the subsequent EMI issue of the collection). The piece includes muted sounds of children playing and is not, it would be fair to say, primarily narrative-driven. Until discovering the ease with which the internet answers just about every question - or offers an answer of sorts, anyway - it had never occured to me to question the lyrics, which I heard as a vaguely themed collection of words linked by the Bowiemeister's own associative process, something like:

Sleigh bells in snow,ie from cinder to coal, coal to cola, cola to koala, koala bears, performing bears, on ice ... the effect, at least in the version I heard in my head, was strangely comforting, like listening to someone's half-formed thoughts, on the edge of sleep, the words, loosed from the shackles of coherence, almost purely musical. Like Wind Chimes by the Beach Boys, perhaps, especially with the final, barely heard refrain on that song ("Whispering winds keep my wind chimes a-tingling ...).

Cinder coal-a bears on ice

Or - to choose another instance at random - the entire canon of Tyrannosaurus Rex (Visconti again).

It never occured to me to check any official sheet music for Some Are - I don't know whether any exists - but looking on the net just now I found a couple of ingenious - alternative hearings, I suppose:

Sailors in snowTo aid the understanding and enjoyment of his unlikely target audience Bowie actually wrote his own notes for the freebie compilation, still readable on the Mail's website, here; I must have taken them in at the time and forgotten them - possibly because they are not really written to be retained once the eye has passed over the page. The notes for Some Are would appear to suggest that in this case there are no mishearings or misreadings - only interpretations Messers Jones & Eno haven't chucklingly thunk up yet:

Send a callout raising hands

Sleigh bells and snow

Cinder-colour blazing eyes

A quiet little piece Brian Eno and I wrote in the Seventies. The cries of wolves in the background are sounds that you might not pick up on immediately. Unless you're a wolf. They're almost human, both beautiful and creepy.A case, you might say, of Sound and Vision On. Blimey, wolves, eh? As Bernie Winters would have said, there's no answer to that.

Images of the failed Napoleonic force stumbling back through Smolensk. Finding the unburied corpses of their comrades left from their original advance on Moscow. Or possibly a snowman with a carrot for a nose; a crumpled Crystal Palace Football Club admission ticket at his feet. A Weltschmerz [world weariness] indeed. Send in your own images, children, and we'll show the best of them next week.

To conclude, the youtube version of Donovan's recording of The Song Of Wandering Aengus with the least annoying visuals, although it's still better if you close your eyes and let your own pictures appear. And if you fall asleep, no matter: as a bit of PR puffery lodged in my mind for almost four decades once claimed of another group: Donovan sells dreams.

He's good here, too, in this 1971 recording from HMS Donovan. He doesn't do much more than deliver the magical words carefully, and in this case that's all that is needed.

Postscript: You can read Ralph McTell's own thoughts on Not Till Tomorrow, the album which featured Barges and Zimmerman Blues, here. He notes that

Barges was the first tune that I could actually trace to another composer, Greig. I rationalised it by saying that “Dawn” was an appropriate borrowing, as my song was about realisation and the beginning of a journey from boyhood to becoming a free man.

As mentioned earlier, the vocals for the album were recorded with a cheap "wonder microphone." McTell ends with a mention of an unexpected email from Visconti:

He told me that he was once again working with David Bowie and had recently acquired a CD of Not 'Till Tomorrow from the internet and was listening back to the recording each day whilst travelling to the studio to record David’s new album. He said he loved the “Low Fi” and all the songs brought back great memories. I wrote back saying that I felt exactly the same.

And there would have been a lovely moment to end - only I forgot about the little matter below. Listen, I've really got to go off and work on the next entry, but you'll know when to pause this clip by yourself, won't you?

Oh, and if an elderly gentleman comes in, just give him your seat, eh? Don't wait not to be asked.

No comments:

Post a Comment