I can't remember when I first heard Stand By Me. It may even have been the Lennon reworking, as my earliest definite memory is of dancing to his version during one of the regular rock'n'roll nights at Tiffany's, Glasgow, in 1975, the enduring Rollin' Joe reassuring us (or himself): "John Lennon's coming home."

But not to have heard Ben E King first just seems wrong: Lennon's may be a great sound (and not one of the Rock'n'Roll album's Spector-produced tracks) but now I can't help hearing it as a cheerfully coarsened version of the original.

As ever, his voice has been treated in some way, and whatever the delights of that bombastic arrangement with its riffing saxophones and humorous guitar quotation, in a sense it's another aural disguise: beneath those two layers of padding Lennon's phrasing (as on just about every cover) has been copied from Ben E King's performance - which may say a lot about his love for the original but doesn't add anything essential to it.

Unless that's the point: if he's basically celebrating a memory, you could argue it's quite right that it should be bigger, louder than the original. And if rearranging places the emphasis on the song and King's voice (as echoed in Lennon's delivery) rather than Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller's production (one wonders at what stage Spector, the great pair's protege, knew of Lennon's plans to record it) the revamped version might even - who knows? - be closer in spirit to the initial idea which King brought to Leiber and Stoller.

King has said somewhere that all the pair (who have co-composing credits) really added to the song was that distinctive bassline, but he was shrewd or humble enough to realise that that was what helped make the record - and ensured his own immortality. (There are other reasons, too, which I'll come to later, why he might not have been minded to raise any objection.)

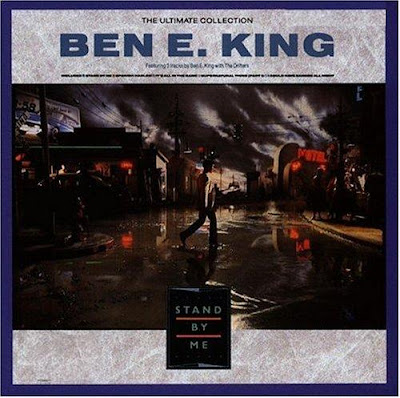

King's own record was first released in 1961, and since then it's never really gone away. Covers (including a so-so one by the then Cassius Clay and a bizarre Mike Yarwood version by Spyder Turner) apart, that same recording was a major hit again in America in 1986, thanks to the rites-of-passage film bearing its name. It took a jeans ad to propel it to Number One in Britain the following year, complete with cash-in compilation (actually a well-chosen selection of Drifters and solo tracks) bearing a still from the ad on its cover.

Did King consider such promotion of his classic infra dig? Probably not in the case of the film, as he participated in a promotional video for the rereleased single featuring its actors - and he has a famously easygoing nature anyway.

That video is an interesting one: an old TV clip of King lipsynching to his hit appears to be revealed as the illustration of a memory related by the modern day performer to a group of students in a lecture hall, unused instruments in the background; two of the film's young stars are cajoled out of that group into coming up and dancing alongside him, then after a few key shots from the Rob Reiner film the group has swelled into a crowd of young and old (the original listeners?) in an exterior location, united by their love of the song.

Well, it sure beats peddling jeans (though I do like the album cover's apocalyptic sky), and even if the promo blurs the line between anthem and cheery singalong it does at least say something about the universality and timelessness of the song. There only appear to be two black faces, each figuring briefly in closeup, among the listeners, which may be stretching universality a bit thin for a song I have seen claimed as a civil rights anthem, although I can't say I've come across much evidence online. They do seem carefully chosen, however: a young man whose presence in the lecture hall becomes more significant if we assume if we're back in the same time period as the film, and a young boy - hope for the future? - in the later crowd.

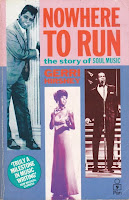

That double whammy of film and TV ad was undoubtedly a force for good in the sense that it gave King back some box office clout, enabling him (I hope) to ditch or limit the kind of gigs he had been reduced to - hotel ballrooms and dinner theatres - when interviewed around 1984 for Gerri Hirshey's book Nowhere to Run. "Not a man given to bitterness or soppy regret", he stresses he is making a nice living and can't complain, talking only of "adjustments" - although his frustration seems pretty clear:

That double whammy of film and TV ad was undoubtedly a force for good in the sense that it gave King back some box office clout, enabling him (I hope) to ditch or limit the kind of gigs he had been reduced to - hotel ballrooms and dinner theatres - when interviewed around 1984 for Gerri Hirshey's book Nowhere to Run. "Not a man given to bitterness or soppy regret", he stresses he is making a nice living and can't complain, talking only of "adjustments" - although his frustration seems pretty clear:"I find them [the audience] very, very hard to reach. Even as many times as I've played it, I still stand in the wings sometimes, and I look out at the audience for a while. They're like forty and fifty and sixty, and the drummer can't get but so loud. And the bass can't get funky. If I say 'funky' to them, I have to explain why I'm doing this."As described in one of the Doo Wop Dialog[ue] entries, it was around that time that I saw him perform in Glasgow, reunited with a cabaret-hardened version of the Drifters - an arrangement which Marv Goldberg says actually lasted for three years of UK tours. Perhaps symbolically, this was not at the legendary Apollo (the Harlem institution's Glaswegian namesake) but in the more sedate setting of the nearby Theatre Royal, home to ballet, musicals and the odd genteel touring theatre production. The support act was a comic, further emphasising the un-rock'n'rollish nature of the event. I wrote in that 2000 post of an onstage culture clash:

while the late Johnny Moore and the others were comporting themselves like so many manic starfish, projecting like crazy throughout, King sort of hugged himself as he quietly, naturally, sang his hits: "Hey, I can't be that person anymore," he seemed to be saying, "but this is as much as I remember. I'm not gonna embroider or patch it up, but what I tell you will be true for me now. If I made it any bigger, I couldn't feel it, so what would be the point?" And it worked; I remember the sense of him giving himself as a real person that night.That may, in part, be sentimentalising, as the voice I thought held in reserve may already have begun to lose some of its power, as had become more evident by the time of the 2001 Leiber and Stoller tribute gig; but that Gerri Hirshey interview still suggests that, whatever the setting, Ben E King will never stiffen into the Archie Rice of Soul. Nor has he salted away all his earnings: as will be discussed more fully later, King has never forgotten his roots and has set up a charity (Leiber and Stoller are honorary chairs) to fund music scholarships for students, among other things. (Listen to some of his most famous songs and learn more here.)

What makes Stand By Me so memorable? It's timeless but also a product of its time, the influences which shaped King and co-composers Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller. Following the trail to its origins even provides a kind of snapshot history of the development and interrelationship of gospel, doo wop and soul.

Benjamin Earl Nelson was born in Henderson, North Carolina, but moved to New York in 1947 at the age of nine, where his father ran a restaurant. For the young Benny, as Hirshey's book puts it, Harlem was

the strange cemented-over place [...] where amateur groups collected under corner streetlamps like sharkskinned moths. Sundays, he recalls, most of the boys sang in church, in storefronts and the solid brick-front Baptist churches that sat along Lennox, Seventh and Eighth avenues like watchful matrons. But until dawn delivered those sweet harmonies unto the feet of the lord, Saturday night bore a wave of voices tuned to the frequencies of earthly love.But despite the national success of doo wop by the time he was singing with his friends on street corners or on subway platforms where "you could hear the sound - your sound - coming right back at you, the way it might on a recording," he emphasises that for him it began as "a neighbourhood thing":

"And if you came up, like so many of us did, from the South, singing could help you get it all together. Turn you into a city boy, you know? I was in two groups most of the time. I sang with an R and B one, but I stayed with the gospel. I mean, for us it was no blasphemy, that kind of garbage. For me the feeling I got was the same. If it was an old church song, one of those old-timey Dr Watts hymns, or a new hit you'd been learning off the records, you took a song and made it your own. And your buddies, the guys who did it with you, they were your heart. You could get so in tune it seemed you all had but one heart between you. Man, you knew when all the other guys were gonna breathe."Nowhere to Run, a history of soul music told through interviews with the artists themselves woven together, as above, by Hirshey's narrative voice, is highly recommended. As mentioned in Doo Wop Shop posts, reading this book and finding details such the above inspired me to write a radio play about a doo wop singer - a composite character, but drawn in part from King's early days. No point in rehashing the whole chapter, entitled Uptown Saturday Night, here, but it's worth hearing about the specifics of those fabled streetcorner days from one who was there:

Benny catches himself for a moment and laughs, a little self-consciously. He wonders aloud if he isn't getting carried away by memories.

"No, no way," he decides. "I really mean it. I would say that those street years, in the groups, were the best of my life. Not the big successes, the gold records, looking at where you are this week in the charts, all that garbage. I mean, that was great, I loved it, and it's fed my family. But listen, it's just real hard to describe now the feeling a quartet gave you. You never felt alone, is all."

"We were pretty cool in my area. We had our fighting crowd - they were the Sultans, mean, ugly, bald headed dudes - and we had our singing crowd. I never really got into fighting. It drove me crazy to have to run like hell for five or six blocks when I could just as easily smile, and doowop, and duck around a corner."Nor was that Chicago group's influence confined to America:

Vocal groups sacked and pillaged, but in a mannerly way.

"My buddies and I would walk from a Hundred Sixteenth to maybe a Hundred Twenty-ninth. And on those blocks alone you'd find anywhere from three to five groups. We'd stop and listen, and if we felt we were better we would challenge them. It was territorial, you know, and you'd have to go out looking for the competition," Benny says. "You'd stand around and check it out; they'd have a crowd anyhow. And their girls of course."

To the victors went their phone numbers. Friday and Saturday nights were the most popular for such musical marauding parties. And no challenge was issued without great preparation.

"We'd learn from the records like everyone did. The group to get you over the best would be someone like the Moonglows. If you could sing Moonglows, you could kill the neighbourhood. They had great harmonies, the Moonglows. Or the Satins or the Clovers. We tried to pattern ourselves after the tight-harmonied groups."

Even in the slums of Kingston Jamaica furture reggae star Bob Marley drew his early inspiration from the Moonglows. There was something about this sound, especially the Moonglows' tight, chesty "blow" harmony, that had tremendous appeal in the post-big band era.Perhaps it's because a 1955 Chess recording provided a kind of stepping stone from the more old-fashioned tones of established black vocal groups like the Inkspots to gospel-inflected doo wop.

In The Heart of Rock and Soul Dave Marsh notes that

For most of its length "Sincerely" might as well be a record by the Mills Brothers or the Ink Spots [...] Only the "vooit-vooit" in the background and a bluesy guitar lick hint that something different might be going on. But, at the conclusion of each verse, the arrangement swings into something more like gospel. This oscillation between church singing and the formalities of Tin Pan Alley-era pop is crucial to the entire ethos of doo wop [...] Sincerely is [...] poised [...] on the fault between profound musical changes.The moments Marsh is talking about leapt out at me, though I wasn't then able to identify what was going on, when I first heard the song around 1978 on the soundtrack album for the Alan Freed biopic American Hot Wax:

But I'll never, never, never, nev-ahhh! Le-het her go...Now I know that Sincerely can be hailed both as a great record and a fine, fine, superfine bit of commercial calculation. The Moonglows were not an Inkspots-type group who had suddenly found a little unexpected fire in their bellies; their earlier sides on the Chance label show they had always alternated ballads with bluesy jumps and wild, gospel-derived singing (2.19 Train, for instance). Bringing the two sides together - and deciding just how much of each to include - was the innovation and the gamble which paid off bigtime.

Talking of paying off leads back to Alan Freed, the legendary and influential DJ whose name not-so-mysteriously appeared on the credits for Sincerely alongside that of Harvy Fuqua; it won't be the last time the issue of composer credits comes up in this piece.

But Freed seems, at least, to have loved the music, and there is a widely held belief that he was made a scapegoat for the payola scandal from which Dick Clark emerged unscathed. If you can afford to buy the DVD box set version of Hail! Hail! Rock'n'Roll!, Taylor Hackforth's Chuck Berry documentary, the superb extras constitute a history of rock'n'roll in themselves, including raw footage of a conversation with Chuck, Little Richard and Bo Diddley. Both Little Richard and Chuck - and do remember this is Chuck Berry we're talking about - speak with immense fondness about Freed.

But Freed seems, at least, to have loved the music, and there is a widely held belief that he was made a scapegoat for the payola scandal from which Dick Clark emerged unscathed. If you can afford to buy the DVD box set version of Hail! Hail! Rock'n'Roll!, Taylor Hackforth's Chuck Berry documentary, the superb extras constitute a history of rock'n'roll in themselves, including raw footage of a conversation with Chuck, Little Richard and Bo Diddley. Both Little Richard and Chuck - and do remember this is Chuck Berry we're talking about - speak with immense fondness about Freed. Er, just to reiterate, in case you didn't quite hear me: that's Chuck Berry, the man obliged to share composing credits of Maybelline with Freed and one Russ Fratto; the man who doesn't walk onstage till the money is on the table or in a stuffed briefcase - or, ideally, a stuffed briefcase on the table. And it was Berry, playing himself in the biopic, as I'm sure I must have mentioned somewhere here already, who said those most magical and unlikely scripted words when told the promoters would be withholding his fee for a Freed concert: "Guess I'll play this one for rock'n'roll." Now that is acting. (When Berry played the Glasgow Apollo in 1975 my Town Hall humiliation brother, then a student reporter, compounded his reputation for egregious gaffery by approaching Berry's management for an interview without proffering a fistful of fivers.)

Incidentally, it is often claimed that Ben E King actually joined the Moonglows. I enquired about this on the Doo Wop Shop board when revising a talk on Stand By Me for my last hurrah as dominie wannabe. In response, someone kindly emailed the transcript of a radio interview with the great man: Benny, it seems, did hang out with the group for about six weeks to get a sense of what they did but eventually realised (this is all from memory) the Moonglows' style meant that even when singing lead his voice wouldn't be spotlighted the way it might in another group - which tends to suggest that for all the self-effacement he had a pretty sure sense of his ability even then.

Presumably this took place some time between coming second at amateur night at the Apollo (Harlem) in 1957 with his local group the Four B's ("Three schoolmates who used to sing around doing harmonies") and being recruited in 1958 for the 5 Crowns by their manager Lover Patterson, as King recalls in this interview with Gary James.

But he wasn't standing around idly in the interim: the Apollo success seems to have propelled him towards the realisation that, with what seemed like "hundreds of groups and a thousand street-corner versions of Earth Angel and Sincerely," the work to make his mark had only begun.

This was to include tuition from the great Cholly Atkins, then a freelance coach, who had already helped the Cadillacs ("So sharp it hurt") perfect their dance moves.In his autobiography Class Act Atkins, later an integral part of Motown's success, explains that choreography for doo woppers was about ensuring longterm survival:

Being asked to join the 5 Crowns proved a particularly lucky break for Benny. Drifters' manager George Treadwell had just fired the remnants of his group (Unca Marvy has details) and needed a new set pronto. King and his new group agreed to step into their shoes - and for many it's this Mk. 2 version which are the - I was going to say "real", but as that's such a contentious issue where the Drifters are concerned, let's settle for the most fondly remembered version of the group, rather than the Clyde McPhatter era Drifters or the UK-revived early seventies hitmakers led by veteran Johnny Moore.Right from the beginning, my ultimate goal with the Cadillacs was to change them into a standard act. At that time, a vocal group was only as good as its last record. If it didn't have a hot record, it wasn't worth too much to the promoters. I wanted to help them make the transformation from rock-and-roll singers into versatile performers, so they would have a wide range of venues available to them.

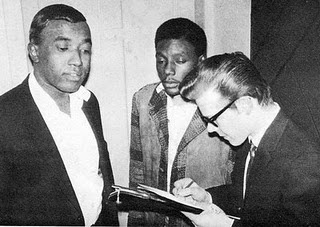

Such broad divisions scarcely seem adequate for a group which must have had over fifty singers pass through its ranks by now; one can understand if Bill Millar, author of a 1971 book about the group, continually puts off work on a revised edition likely to be out of date before it hits the shelves. (Is there a website devoted to this Sisyphean task?) Not to mention the questionable legitmacy of lots of Drifters, er, variants which could be discussed at length ... Millar is pictured, below, doing his own sleuthing; as an Australian blogger notes: "he looks like a chap who's not going to give up till he nails the matter, no matter how discomfited his subjects may be."

But as determining where the Drifters end and "tribute" acts begin could addle any brain other than the mighty Millar's, and as we have a song to aim towards, better to concentrate on the fact that Ben E King and his fellow Crowns (the new moniker an allusion to the group name?) were not themselves expected to function as a glorified tribute act to McPhatter's old group, and instead were given fresh material to record from the best of the Brill Building writers including Leiber and Stoller, their initial producers.

"It all came together in Clyde," Benny says [pictured with McPhatter, above, in 1972]. "He could sing the blues, but he had that gospel sound since he came up in church. What Clyde did was to bring gospel into pop in a big way as a lead singer. I guess you could say he made a wide-open space by mixing it up like that. A space a lot of guys were grateful for."

This is a sentiment echoed in Owen McFadden's BBC radio series on doo wop, Street Corner Soul, where more than one interviewee says something to the effect that while they liked Sonny Till, McPhatter (below, in his pomp) had the whole package: voice, babe-magnet good looks and excitement; they admired Till's voice but they never actually wanted to be him.

The conclusion of Millar's book, written when Clyde McPhatter was still alive and had hopes of reviving his career, succinctly sums up the importance of his contribution to the development of doo wop:

The conclusion of Millar's book, written when Clyde McPhatter was still alive and had hopes of reviving his career, succinctly sums up the importance of his contribution to the development of doo wop:

McPhatter took hold of the Inkspots' simple major chord harmonies, drenched them in call-and-response patterns and sang as if he were back in church. In doing so he created a revolutionary musical style from which - thankfully - popular music will never recover.

And if you seek his monument, try listening to the restrained hysteria of The Bells, a possible influence on King's vocal in Stand By Me ...

... or place the Ink Spots' and the Dominoes' versions of When the Swallows Come Back to Capistrano side by side.

Aaron Neville, quoted on the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame's page on McPhatter, inducted in 1987, said:

Anything Clyde sings is a prayer. When I was growing up, I don’t care what else was going on in the world - Jim Crow, all the other stuff - you could put on Clyde McPhatter and it would all disappear.Whatever McPhatter's stylistic innovations, however, by the late fifties increasingly sophisticated production techniques were encouraging wider change: it was the sound of a record which sold, not its fidelity to the artist as heard live. King's first lead in 1959 with his version of the Drifters, There Goes My Baby, is of considerable historical significance in this respect:: like Sincerely, it has a foot in two camps.

Incidentally (again), Charlie Thomas, the intended lead, either got the studio equivalent of stage fright or couldn't pick the song up quickly enough from Benny to satisfy Leiber and Stoller (like Stand By Me the composition is credited to all three) and King was eventually asked to take over - an historical moment in itself, as according to an "audio biography" on the CD issue of The Beginning of It All he hadn't thought of himself as a lead singer until then - which makes my memory of his Moonglows-related interview less reliable.

King, forced to sing at the top of his range, delivers a great gospel/doo wop lead and the rest of the group are doing the usual doo wop type backing, but that arrangement is something else. It came about because a recording session with Leiber, Stoller and arranger Stanley Applebaum was falling apart so they started to "fool around", as Jerry explains in an interview quoted by Millar:

Stanley wrote something that sounded like some Caucasian take-off and we had this Latin beat going on this out of tune tympani and the Drifters were singing in another key, but the total effect - there was something magnetic about it.Leiber and Stoller played the tapes back to Ahmet Ertegun and Jerry Wexler; Wexler famously spat out his tuna sandwich in disgust but Ertegun bowed to the producers' insistence that there was something amid the mess - and the song proved a huge hit - even if Leiber himself, hearing it later on the radio, was "convinced it was two stations playing one thing." (Millar observes that Leiber may have meant one station playing two records as "the effects were multi-dimensional.")

Strings were not entirely new in rock'n'roll or doo wop. Since I Don't Have You had come out with a luscious arrangement the previous year, making the Skyliners the first white group to top the R&B charts (and provide a hint or two for the young Phil Spector) but they were the exception. As Millar says:

The strings on There Goes My Baby were not the dull, weepy violins used on popular recordings by white singers for the past twenty years. They rose and fell with a stark, triste and postitive allegiance to classical music. With justification the song might have been called There Goes Tchaikovsky. Kettle drums pounded throughout, but more obviously during the deeper, quieter moments of the string passages, strengthening a reseemblance to the 1812 overture. It is an interesting coincidence that, like the works of the Russian composer, There Goes My Baby can also be described as "notable for a vivid, forceful scoring and for an often expressed melancholdy." Ben E King sang in a higher key than his normal baritone range. The effect was two-fold: it heightened the coarse, untrained, root-gospel quality of his voice and imparted an air of hopelessness to the theme of the song.

[...] There Goes My Baby was instrumental in bringing the Drifters from the comparative obscurity of the large but segregated black commnunity into popularity in over half a million white homes. For an inexperienced but inglorious group, The Crowns had it made. They bowed daily in the direction of The Atlantic Record Corporation for ever more.

Which may provide another reason why King immediately understood the signiificance of Leiber and Stoller's contribution to Stand By Me. It's not too difficult to reimagine There Goes My Baby as a straight doo wop record, on some little indie label, a local hit, perhaps; it needed the happy discovery of that astonishing setting (dubbed "beat concerto" by the music press), to achieve crossover success, even though others may feel, as I do, a certain sadness in acknowledging the greatness of this production. Its influence helped spell the death knell for a simpler era of recording where the overall sound was less important than the thrill of hearing four or five voices blending together.

Still - it's gone. As my Cheapo gaffe friend's nephew would say: face it. There Goes My Baby, like Stand By Me, looks forward to soul and, ultimately, the Motown assembly line approach. And it was another brick in Uncle Phil's Wall of Sound, as according to the Rolling Stone Encyclopedia "Phil Spector studied this production model under Leiber and Stoller, working on The Drifters' records"; perhaps, indeed, that was the 45 which inspired Phil's vision of "little symphonies for the kids," even if it was Wagner he cited rather than Tchaikovsky.

But it's not simply the sound of There Goes My Baby which prefigures soul: the song itself, the starkness of such lyric as there is, feels a world away from the "well-worn satchel of cliches" (the Encyclopedia's description of Come Go With Me) which can make up a doo wop record. But the tone doesn't quite match that of non-crossover rhythm and blues songs either, leavened as they often are with a knowing wit, a worldliness; it's closer to a rawer, earlier blues.

Or gospel.

continues next post

No comments:

Post a Comment