Listening to Ian Whitcomb's show (see previous post) reminds me that, important as my local library may have been in encouraging my listening to music beyond rock and pop (even if it was mainly down to their snooty refusal to stock that kind of thing), I haven't yet discussed the broadcasters who stepped in to ensure that my ears, unlike those of the young Bing Crosby, remained pinned back thereafter.

It never occured to me, or I felt too intimidated, to approach the librarians for advice about the music I was borrowing. More likely the latter: I was around thirteen, fourteen; the assistants, in their early twenties at least, seemed superior and unapproachable. I always felt a vague sense of guilt and shame anyway about the act of borrowing records, as I never did about books: it seemed to be a case of getting something for nothing, a loophole which might be closed any day now so I'd better keep my head down and not attract attention to the goodies which I was regularly sneaking out the door.

Timidity/irrationality apart, it's quite possible the younger librarians had little interest in most of the stock, which seemed to have been chosen by a more senior individual, reflecting his tastes (it had to be a he) growing up in the fifties during the British trad jazz boom to which the Beatles and their ilk later put paid. (John Lennon's pet hates in one of those pop mag questionnaires: "Trad Jazz and thick heads.")

Anyway, borrowing continued unabated but uninformed until my gradual discovery of a handful of radio presenters whose tastes ran to such genres as were condoned by the library. It was then that I began to see how those randomly selected pleasures fitted into a bigger picture, encouraging me to start reading about music as well as listening more widely.

Not that the kind of radio shows I'm talking about simply delivered straight jazz. I had developed a liking for nostalgiac music in general, also fed by whoever filled those shelves. As well as jazz and folk you could borrow music hall LPs, even blues; it was only pop - nasty, raucous pop, and rock'n'roll too brash to hide behind the blues label - which they didn't like.

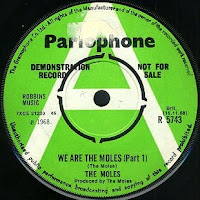

(Diversion: I actually happened to be listening to Radio One when the Moles, believed to be an alias for the Beatles, were being interviewed. Was it Stuart Henry's show? And were they actually in the studio? If memory serves, we were told they had paper bags over their heads. "so why are you called the Moles?" Henry, or whoever, asked. "Because we're underground," a band member replied. If only I'd had a drum and cymbal to hand ... )

As an example of the rigid divisions in operation, I first heard Joe Turner's The Boss of the Blues via Motherwell Library, but scanned the shelves in vain for an accompanying greatest hits compilation with tales of inquisitive one-eyed cats. Maybe I should have told them that even Humphrey Lyttleton liked Big Joe's rock'n'roll side (he'd toured with Turner) so it was alright.

Already familiar with Little Richard, it was odd to hear Turner's Roll 'Em Pete (in that 1956 Atlantic version) and realise that here was an equivalent excitement achieved by different means: too long ago to remember the quotation but I think in one of Lyttleton's books he talks about Big Joe sitting on a stool rather than indulging in any Pennimanian antics yet gradually whipping the audience into a similar frenzy by sheer perserverance. I do remember, however, that Lyttleton, or possibly someone else, recorded his surprise that despite a career going back to the thirties, and stretching far beyond the fifties, it was only Big Joe's comparatively brief incarnation as a rock'n'roll star which he remembered as the Good Times.

Having said all that, much as I respected Humphrey Lyttleton and listened to his longrunning programme The Best of Jazz from time to time, he isn't one of the presenters who made a real impact on me. Whether that's because his programme had to cover too wide a period of jazz (Charlie Christian is about my limit) I'm not sure; but I draw attention once more to his book of the same name (originally two volumes, now published as one) which describes Luis Russell's Panama and does a great deal to make the history of jazz and some key early sides accessible to the average reader.

I'd give a wide berth, however, to a recentish book of anecdotes called It Just Occured to Me - it's the kind of thing which will pass an hour or two if picked up in a library (I bet Motherwell has it, if that Great Purchaser hasn't been put out to pasture) or very cheaply in a remainder bookshop but you'd resent paying full whack for it. Or I would, and I did.

This may be unfair, as the book which discussed the tour with Turner (possibly Take It From the Top, although I'm not sure) was the same kind of thing, only I remember that more fondly - especially his description of sitting silently with Louis Armstrong in his dressing room, sharing an understanding, before showtime - so maybe my tastes have changed. Dunno. But I did get that one from a library.

The original two volumes of The Best of Jazz (earlier editions of Vol 1 shown above) were entitled From Basin Street to Harlem (chapters on recordings by the Original Dixieland Jazz Band, Bessie Smith, Duke Ellington, Luis Russell, Louis Armstrong and others) and Enter the Giants (Billie Holiday, Fats Waller, Art Tatum, Coleman Hawkins and many more). They are, as I say, intended for the general reader, so he's careful not to get too technical when describing music, but the pleasure of reading the book(s) is your awareness that here is the bottled essence of what was at the time over four decades of Humph's living and breathing jazz. I won't go on, as this is straying too far from my intended subject, but may return to this another day.

The doo wop-dedicated will have worked out that we are also straying from the rock'n'roll/R&B field for this entry. That's because I mostly discovered doo wop for myself through the process of trial and error described earlier. Unlike those fortunate future Beach Boys, there was no Mike Love was on hand to initiate me into the delights of late night listening to Johnny Otis on KFOX. Whose reach probably didn't extend to the West of Scotland anyway.

And in the case of 60s/70s pop and rock, although I listened to a lot of BBC Radio One DJs in the seventies, those nights spent with John Peel and others whispering in my ear didn't have the impact of an new discovery: they were building on knowledge already acquired from my elder brothers and reinforced by the weekly TV rituals of Top of the Pops and The Old Grey Whistle Test.

What did reach the West of Scotland around 1974, however, was a new local non-BBC radio station called Radio Clyde. I don't know what it's like now, but then there were some wonderful programmes to which I listened regularly. Well, some, like Drew Moyes's Folk and Suchlike, I fully intended to listen to regularly but somehow never did. I taped the first one but the next broadcast I listened to happened to fall on the show's anniversary when, as a special treat, they played ... the first broadcast.

I'd give a wide berth, however, to a recentish book of anecdotes called It Just Occured to Me - it's the kind of thing which will pass an hour or two if picked up in a library (I bet Motherwell has it, if that Great Purchaser hasn't been put out to pasture) or very cheaply in a remainder bookshop but you'd resent paying full whack for it. Or I would, and I did.

This may be unfair, as the book which discussed the tour with Turner (possibly Take It From the Top, although I'm not sure) was the same kind of thing, only I remember that more fondly - especially his description of sitting silently with Louis Armstrong in his dressing room, sharing an understanding, before showtime - so maybe my tastes have changed. Dunno. But I did get that one from a library.

The original two volumes of The Best of Jazz (earlier editions of Vol 1 shown above) were entitled From Basin Street to Harlem (chapters on recordings by the Original Dixieland Jazz Band, Bessie Smith, Duke Ellington, Luis Russell, Louis Armstrong and others) and Enter the Giants (Billie Holiday, Fats Waller, Art Tatum, Coleman Hawkins and many more). They are, as I say, intended for the general reader, so he's careful not to get too technical when describing music, but the pleasure of reading the book(s) is your awareness that here is the bottled essence of what was at the time over four decades of Humph's living and breathing jazz. I won't go on, as this is straying too far from my intended subject, but may return to this another day.

The doo wop-dedicated will have worked out that we are also straying from the rock'n'roll/R&B field for this entry. That's because I mostly discovered doo wop for myself through the process of trial and error described earlier. Unlike those fortunate future Beach Boys, there was no Mike Love was on hand to initiate me into the delights of late night listening to Johnny Otis on KFOX. Whose reach probably didn't extend to the West of Scotland anyway.

And in the case of 60s/70s pop and rock, although I listened to a lot of BBC Radio One DJs in the seventies, those nights spent with John Peel and others whispering in my ear didn't have the impact of an new discovery: they were building on knowledge already acquired from my elder brothers and reinforced by the weekly TV rituals of Top of the Pops and The Old Grey Whistle Test.

What did reach the West of Scotland around 1974, however, was a new local non-BBC radio station called Radio Clyde. I don't know what it's like now, but then there were some wonderful programmes to which I listened regularly. Well, some, like Drew Moyes's Folk and Suchlike, I fully intended to listen to regularly but somehow never did. I taped the first one but the next broadcast I listened to happened to fall on the show's anniversary when, as a special treat, they played ... the first broadcast.

I did make a regular appointment for Dick's Midnight Surgery - maybe not quite wall-to-wall wonderful, but he played a lot of 50s and 60s pop, which at the time I devoured indiscriminately, and seemed to be a personal friend of Del Shannon, who was forever making guest appearances. Richard Park (left) has gone on to Greater Things, so I'm not sure whether that means his heart wasn't in it - he also co-presented a sports phone-in at the weekend, although the real star was the acerbic Jimmy Sanderson, famous for becoming highly confrontional with fans. I have just found this supposed example of Sanderson in action quoted on a forum about football phone-ins - even if it's an exaggeration it does suggest the authentic Sandersonian manner:

I did make a regular appointment for Dick's Midnight Surgery - maybe not quite wall-to-wall wonderful, but he played a lot of 50s and 60s pop, which at the time I devoured indiscriminately, and seemed to be a personal friend of Del Shannon, who was forever making guest appearances. Richard Park (left) has gone on to Greater Things, so I'm not sure whether that means his heart wasn't in it - he also co-presented a sports phone-in at the weekend, although the real star was the acerbic Jimmy Sanderson, famous for becoming highly confrontional with fans. I have just found this supposed example of Sanderson in action quoted on a forum about football phone-ins - even if it's an exaggeration it does suggest the authentic Sandersonian manner:Jimmy Sanderson - Were you at he game today, caller?

Caller - No.

Jimmy Sanderson - Why not?

Caller - It was my wife's funeral today.

Jimmy Sanderson - What time was the funeral at?

Caller - 11 o'clock.

Jimmy Sanderson - No excuse - you still had plenty of time to get to the game.

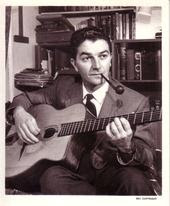

The person I remember most fondly from Radio Clyde and those long-ago seventies nights listening to the radio in bed is Ken Sykora (above and, in younger days, top).

I'm aware now of his distinguished career in music and broadcasting - you can find, here, a myspace page set up by his family with photographs and some examples of his guitar playing; he loved Django Reinhardt and wrote the sleevenotes for a superb Hot Club compilation (below) which I later discovered. The young Paul McCartney listened to his BBC radio programme Guitar Club in the fifties, which also featured Ike Isaacs, who later played with Jake Thackray.

At the time, however, he was - for me - an unknown quantity, although I quickly became aware he possessed an intimacy of manner perfectly suited to late night listening, fostering the illusion that the broadcast was intended solely for you.

The title of his programme, Serendipity with Sykora, allowed him to play whatever he wanted, assuming some chance connection with the previous piece could be found, and the result was a beguiling mixture of novelty songs and jazz, knitted together with odd anecdotes and what came across as an absolute ease in the studio. I really wish I'd taped some of those shows at the time; alas, I have no record of any of them. It felt like a friend was informally guiding you through some records he happened to like, saying whatever came into his head about them or any loosely related matter, wholly at ease.

He was very fond of Peggy Lee but it's the oddities I remember: it was Serendipity which introduced me to Spike Jones and His City Slickers, in particular Cocktails for Two - not too difficult a leap for one brought up on the Bonzo Dog Doo Dah Band on the telly. Here's a film short where it's acted out:

Some records such as Hoagy Carmichael's version of Barnacle Bill the Sailor straddled the novelty/jazz divide, with Bix Beiderbecke and others blowing wildly between the verses - and Sykora had an eye for the pleasing detail, informing us that the use of a rude word - "I can't swim a bloody stroke" - had caused this to be banned at the time.

I see, by a quick scamper round the net, that the group was formed by Cliff Adams of Sing Something Simple fame. This was a programme symbolic of the old BBC Radio 2 and its predecessor the Light Programme. Sing Something Simple administered a kind of musical valium - parlour songs and pop songs were all remodelled to sound more or less the same. Yet I have to admit I listened to it, on and off, over the years, so I don't know where I'm getting that snooty attitude from. The show remained in the Sunday afternoon schedule for decades until Adams' death, whereupon the whole of Radio 2 seemed to change. I think Cheerful Charlie Chester died around the same time, and his half make-believe 1940s world of people forever being kind to each other and offering unwanted typewriters for free via the programme did not endure for long after that. (These days if it's not new, no one wants to know - even in Britain.)

I see, by a quick scamper round the net, that the group was formed by Cliff Adams of Sing Something Simple fame. This was a programme symbolic of the old BBC Radio 2 and its predecessor the Light Programme. Sing Something Simple administered a kind of musical valium - parlour songs and pop songs were all remodelled to sound more or less the same. Yet I have to admit I listened to it, on and off, over the years, so I don't know where I'm getting that snooty attitude from. The show remained in the Sunday afternoon schedule for decades until Adams' death, whereupon the whole of Radio 2 seemed to change. I think Cheerful Charlie Chester died around the same time, and his half make-believe 1940s world of people forever being kind to each other and offering unwanted typewriters for free via the programme did not endure for long after that. (These days if it's not new, no one wants to know - even in Britain.)Yeah, I was just thirteen, you might say I was a

Musical proverbial knee-high

When I heard a couple new-sounding tunes on the tubes

And they blasted me sky-high

And the record man said every one is a yellow Sun

Record from Nashville

And up north there ain't nobody buys them

And I said, but I will ...

I can remember the keen pleasure of the programme, the seemingly endless new (to me) discoveries it contained, but I've no idea how long it ran. I've got a feeling, in fact, that he was shifted to an earlier slot for a programme specifically about the big bands, but have no idea whether this was a matter of choice. I enjoyed that programme, too, although it meant the element of unpredictability which made the Serendipity show so enjoyable was lessened. Oh, and I forgot to mention that, like Ian Whitcomb, he was partial to Hawaiian music too - not to mention the odd bit of double entendre as enjoyed in more recent years by Earl Okin. It strikes me now how artfully assembled his programmes were: those novelties were a way of hooking the casual listener into a programme which, like Ian Whitcomb's, had no artificial musical divisions.

He went on to work in other capacities for Clyde as the obituary on the myspace page says. But what was most important about his programme and those presented by the others who I'll discuss in a later entry was a sense that the music and personality were one and the same - that you didn't wait for one to be over so you could enjoy the other - and that you were happy, above all, simply to spend time in his avuncular company. His sign-off - "From me, Ken, adios" - always seemed personal to you.

To balance out the novelty songs above, an early side from his favourite Peggy Lee, singing with a Benny Goodman small group. I don't specifically recall hearing this on his programme but the sensation I got recently when hearing it on the BBC Radio 4 programme Desert Island Discs (the choice of Joan Bakewell) felt like a memory of those many serendipitous finds to which he introduced me. Talking of a roughly contemporary recording, a reviewer once compared Lee's voice to "a moon crossing a cloudless sky, silent, steady but oh so hypnotically entrancing." This Rodgers and Hart song has been covered by many artists, including Dion and the Belmonts, but has anyone ever sung it quite like this?

I'd distinguish my favourite presenters from those to whom the music merely seemed an aspect of the marketing of their personality. Jimmy Saville (right), once asked whether music was important to him, replied something like: it's woven into the fabric of my suit - which I'd be strongly inclined to take as a no. Especially when he saw no shame in revealing that he would toddle along to Broadcasting House and record a two hour radio programme in half an hour - ie he didn't listen to the music and "Uncle" Ted Beston or whoever his producer was would subsequently edit everything together. And a bit like Kenneth Williams playing for time on Just A Minute he had a forumula to string out his links: "1964 ... it was. The Dave Clark Five ... it was."

I'd distinguish my favourite presenters from those to whom the music merely seemed an aspect of the marketing of their personality. Jimmy Saville (right), once asked whether music was important to him, replied something like: it's woven into the fabric of my suit - which I'd be strongly inclined to take as a no. Especially when he saw no shame in revealing that he would toddle along to Broadcasting House and record a two hour radio programme in half an hour - ie he didn't listen to the music and "Uncle" Ted Beston or whoever his producer was would subsequently edit everything together. And a bit like Kenneth Williams playing for time on Just A Minute he had a forumula to string out his links: "1964 ... it was. The Dave Clark Five ... it was."  It may or may not be true that Saville was the first person to introduce the idea of playing records in dance halls in the North of England, and he was an ebullient presence in my earliest viewings of Top of the Pops, but never what you'd call an enthusiast. The only music he ever seemed to feel emotional about was Ray Charles's I Can't Stop Loving You, played to honour his late mother, known as the Duchess. A notoriously wily TV interviewer did a documentary about him but was outmanoeuvred at almost every turn; Saville had about four decades' start of telly manipulation on him.

It may or may not be true that Saville was the first person to introduce the idea of playing records in dance halls in the North of England, and he was an ebullient presence in my earliest viewings of Top of the Pops, but never what you'd call an enthusiast. The only music he ever seemed to feel emotional about was Ray Charles's I Can't Stop Loving You, played to honour his late mother, known as the Duchess. A notoriously wily TV interviewer did a documentary about him but was outmanoeuvred at almost every turn; Saville had about four decades' start of telly manipulation on him.But look, I didn't come here to talk about Jimmy Saville either. Nor one of the Radio One DJs later consigned to the dustbin of history who famously didn't have a record player at home. Rather than rush through this, I'll take a break and come back with more about some other key figures in my education: Hubert Gregg, Benny Green, Russell Davies and Dilly Barlow (left to right, below).

Of this influential quartet, sadly, Hubert Gregg and Benny Green are now dead, and Dilly Barlow is now a much in-demand voiceover artist.

Russell Davies, still broadcasting, inherited Benny Green's radio slot on Sunday afternoon before being shunted to the evening (now Ms. Elaine Paige holds sway in the afternoon presenting a less imaginative but presumably more popular devoted solely to well-known musicals). I wrote to him once, thanking him and, by extension, those others in an unbroken line from Ken Sykora who had helped open this wider world of music for me.

Russell's programme (find information and listen to broadcasts for up to one week on the BBC page here) focuses on the great (mostly) American songbook with an emphasis on singers, rarely playing instrumental versions, so it was pleasing and touching, not long afterwards, to hear him play a Sykora recording by way of his own tribute to a great broadcaster.

You can hear Honeysuckle Rose - nodding to, but not slavishly copying, his beloved Django - at the Ken Sykora myspace page here. Adios, Ken.

Part On: Ian Whitcomb

Part Three: Hubert Gregg

Part Four: Benny Green & Robert Cushman

Part Five: Russell Davies

Part Six: Those Unheard or There is a Balm in Islington